Vietnam’s Pharmaceutical Sector

Vietnam’s Pharmaceutical industry – A sector of high potential

Vietnam Pharmaceutical market is estimated at 7.7 Billion USD this year with a 16% CAGR (2012 – 2021), more than double that of the nation’s GDP (7%). Compared to neighboring economies, the low average of pharmaceutical spending per capita is suggesting more room for future growth. The market value is projected to reach 16.1 Billion USD in 2026[1].

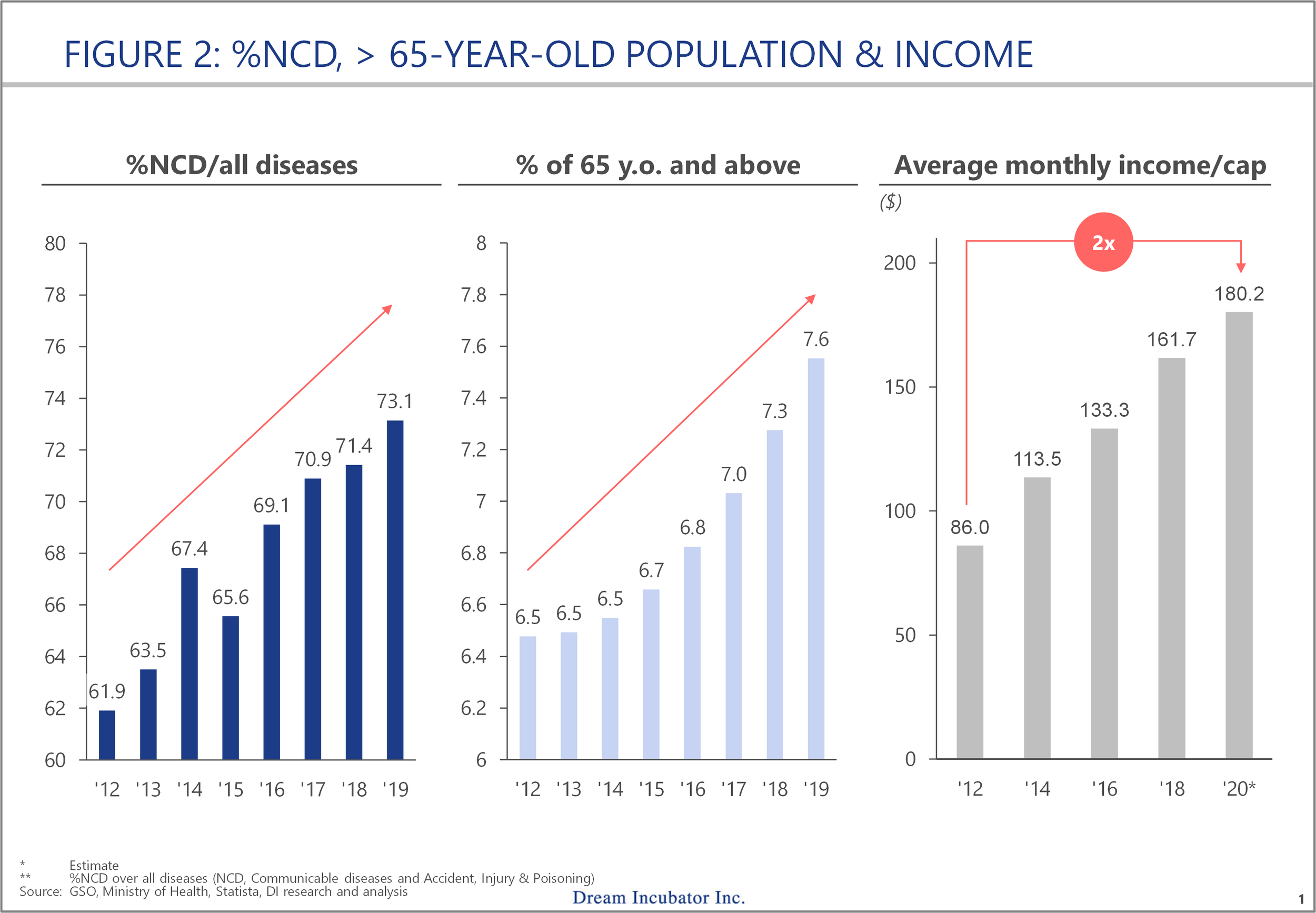

The increase in Non-communicable diseases (“NCD”), aging population and income are believed to be the major market drivers. According to Vietnam’s Ministry of Health, the number of NCD cases recorded in Vietnam is surging. Cardiovascular and Cancer are reported to be the most common death factors. Besides, aging population (above 65-year-old people) is also rising quickly in recent years, triggering higher demand for eldercare. At the same time, average income also doubled between 2012 and 2020. Higher income is expected to boost Vietnamese consumers’ awareness towards new demands for high quality healthcare and preventive healthcare including spending on wellness products such as vitamins and nutrition.

Market fragmentation affects medicine price and quality

Similar to other emerging countries, Vietnam’s pharmaceutical market is facing fragmentation in the distribution chain. Our research shows that before consumption, there are at least 3 distribution layers with multiple players, which prevent medicines from being properly controlled in both terms of price and quality.

High medicine price

A direct consequence of the fragmented distribution chain for Vietnamese consumers is high medicine price. There is a huge difference comparing local consumers’ price versus international reference price of originator brands. In some cases, it can get up to 47 times higher[1].

The first factor is high import costs

Local manufacturers’ lack of production capacity and capability results in a modest demand coverage of 36%, of which most medicines are generic. Consequently, more than half of the market value is from imported products, especially branded drugs. It is estimated that about 20% of retail price is from the costs of importation.

The second is high distribution costs (for sales representatives & logistics)

It is estimated that Vietnam has roughly 10,000 clinics and 57,000 pharmacies, of which 98.5% are independent and small. Therefore, distributors-retailers is not as simple as a one-to-one relationship but in fact, a many-to-many. This multiplies the cost paid while they work together. Take fee for sales representatives[1] as an example. Given the large number of retailers scattered around the country, distributors and manufacturers must have a proportionate number of sales representatives to cover them all. Thus, this multiplies the cost spent on sales activities per revenue generated. It is estimated that the number of sales representatives required to generate 10 million USD is 55 in Vietnam, while the US needs only 3.

Such spider-web distribution network also makes logistics costly. In Vietnam, there are roughly 1,500 distributors, but none is having a sufficient medicine portfolio for any pharmacy. As an image for comparison, in the USA, 3 major distributors are accounting for roughly 90% of the market supply. On average, one pharmacy in Vietnam works with at least 5 suppliers to secure enough items for its retail purpose. That makes delivery costly. The cost is even higher for small and rural pharmacies because their orders are in small-quantity and distances are longer. Even if extra shipping cost can be compromised, not all distributors agree to ship to them, especially big brands, whose minimum order quantity is often too high. “Most small pharmacies do not even have Pfizer medicines”, said a founder of a B2B distribution startup in an interview with DI about same topic. With no other options, pharmacies and clinics must resort to wholesale market clusters to centralize buying orders and have access to big-brand products. This begets another pain of medicine quality for consumers.

Uncontrolled medicine quality

Medicines sourced from wholesale markets often have unknown origins and contain the risk of being counterfeit. According to a pharmacist working in Ho Chi Minh City’s wholesale market, no pharmacist at this market knows exactly from where the store owners source medicines. “Sourcing always happens in private”[1]. As reported by local news, from 2014 to 2018, more than 80 counterfeit medicine cases were discovered during market inspection in Vietnam[2]. The quality control problem could be more severe due to the lack of inspection staff, as recorded by Vietnam’s Government Inspectorate.

New business development has already been in progress

Leading players have been very active in addressing the above issues to unlock the full potential of the sector. As for pharmaceutical companies, the key focus is product R&D via new establishments of manufacturing factories and supply chain management. This promises to increase domestic supply capacity and reduce price. As for retailers, chains have emerged and are being standardized to meet the government’s GPP[1] requirements. This guarantees consumers with quality-assured medicines. Given those dynamics in the sector, robust investment activities in recent years were recorded.

Apart from the movements of traditional players, the rise of health tech startups is also worth noticing. These players are expected to solve market issues and disrupt the current situation in the distribution chain with new business models and service offerings. The new digital solution trend is also attracting much attention from Venture capitalists.

One example is a digital distribution business aiming at building an effective distribution channel for retailers. On a single digital platform, Thuocsi.vn connects medicine suppliers (Manufacturers and distributors) directly with retailers (Pharmacies and clinics) thus eliminating the hassles from multi-layered supply operations. The delivery service that comes along with the platform is highly appreciated by retailers, especially rural ones. By aggregating small-quantity orders, it reduces shipment fee. Small pharmacies and clinics can now purchase without the pressure of meeting the minimum order quantity from big brands by mixing different SKUs from different suppliers.

Some other startups solve the problems not only in distribution but also in providing medicine information, promotions, and business data collection, all of which are traditionally overseen by sales representatives. POC Pharma is an example for this. This Vietnam and Hong Kong-based startup offers pharmacies in Vietnam a SaaS solution to digitize and automate pharmacy business management. It helps pharmacies better manage their businesses with real-time inventory report and reduce manual labor on stocks and sales management. This SaaS is also an effective communication channel between suppliers and pharmacies. On this platform, product information and promotions can now be sent straight to pharmacies and sell-out data can be collected directly without going through sales representatives.

Under the current circumstances, it is promising that heath tech start-ups (including pharmaceutical businesses and other healthcare branches) are expected to grow in both quantity and quality.

About the Authors

The article is co-authored by a DI consultant team

Hoang Thi Tram Anh, Manager